Attentiveness: Evangelicalism–Ad Fontes!

Entropy can set in so easily. In fact, it is the standard trajectory of all of creation. Things go from a place of higher energy to lower. Buildings decay, batteries wear down, and even my body seems to be wearing down.

Institutions and words can also succumb to entropy which can show itself as mission-drift or meaning-drift. An institution is established for a particular purpose or meaning and, over time, it drifts into other areas. This might be due to the need for sheer survival or perhaps the search for ongoing relevance. Words drift and lose the power of their meaning. They devolve to a lower level of meaning and lack precision. At times they almost become meaningless.

And so, before our upcoming conference on “Evangelicalism, Identity, and Culture,” I reflect for the fifth time in four years on the term “evangelical” and how its meaning has drifted, or lost its clarity.

In preparing for this important conference, I have been reminded of some important lessons from one of my church history professors, Dr. Richard Lovelace. One of the speakers at our conference, Collin Hansen, writes that Lovelace was one of the most influential professors for the late-Tim Keller during his years at Gordon-Conwell. I believe the reason for the long and broad shadow cast by Lovelace is because his teaching encapsulated what has become our understanding of life in Evangelicalism.[1] Just a few characteristics I am reminded of that should help us fight the entropy that is draining the word of its meaning and thus its power.

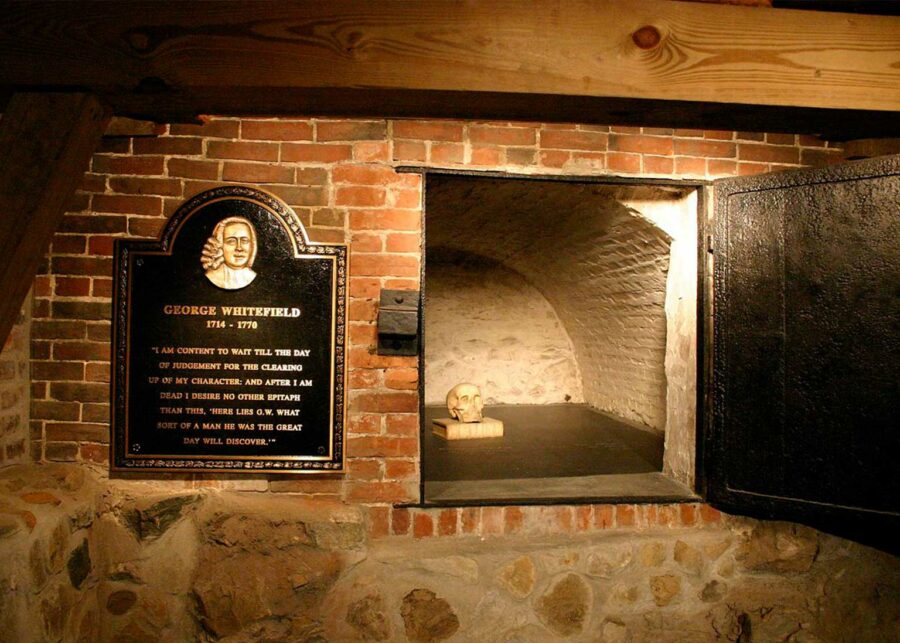

- Evangelicalism always has a uniting dynamic empowered by the Holy Spirit. One of the great criticisms of George Whitefield, who began his great preaching tours in America at the age of twenty-three in 1738, was that he uncritically supported Congregationalists, Anglicans, Presbyterians, Dutch Reformed, Lutherans, and Baptists at his rallies. Not only did the Spirit unite denominations, it united upper and lower-class people, and even reached slaves, indigenous tribes, and villages. Whitefield’s rallies looked more like Revelation 7 than like New England villages that were first founded by specific religious groups.

- Evangelicalism has always assessed the human condition and solutions to the human condition with clarity. “Awakenings” occurred when people became awakened to their sinful condition and realized that under God’s righteous and holy hand, they deserved judgment. Fear of a mighty and righteous God leads to a solution of pure grace, from first to last. No holy works can solve the deep problem; only God’s love can so overwhelm us into his Kingdom of love.

- Evangelicalism leads to holiness. The result of awakenings in the past has been personal sanctification and social rectification. The Spirit convicts, converts, and corrects both persons and cultures. The result of Evangelical revivals is always the beginning of gospel-centered social engagement. One of the great taproots of Evangelicalism is the Puritan movement that insisted on everyone—men and women—having full access to Jesus through the Bible. Not the priest, nor the church itself, but God’s Word was authoritative and, therefore, it must be read, re-read, and obeyed. As a result, there were more books per person in Puritan New England in the seventeenth century than anywhere else in the world at the time. Literacy is the foundation for social improvement.

- Evangelicalism is a movement that, like all movements, either “rationalizes”[2] into formulaic structures and institutions or it slowly dissipates or burns itself out (entropy). This process of rationalization may preserve the movement, but at times it extinguishes what it hopes to preserve. Evangelicalism has a great tradition and has done great things. It has created a legacy of a remarkable number of colleges, seminaries, churches, denominations, benevolent societies, hospitals, and missions. In fact, Evangelicalism has been known by its activism in society and its creativity in forming institutions that impact local communities and the Kingdom. Personal holiness led to social holiness.

Yet, despite this remarkable history and these signature features of historical Evangelicalism for which we can hold our heads high–like a river hitting the plain, the movement (and its many institutions) has spread out and become disparate, shallow, and unwieldy: entropy has set in. The time is right for a historical corrective and a return to these honorable roots. Ad Fontes! Back to the sources!

It is worth reflecting on some of these themes in recovering some of what has been lost in the current complex and (at times) contradictory iteration of Evangelicalism today. I like to think of Evangelicalism as directed by John 15, John 17, Matthew 25, and Matthew 28: missional, unitive, evangelistic, benevolent, and Spirit-driven. So, while we cannot create a revival, we can ensure our institutions create the preconditions for revival such as Dr. Lovelace would talk about. These preconditions include an awareness of the holiness of God and sinfulness of humanity. This is a good place to start our recovery.

I can almost hear Dr. Lovelace poetically intone, “We can’t create a revival or awakening, but we can live such lives that invite God’s Sprit to do only what He can do.”

[1] This is most powerfully articulated in his best-selling tome, Dynamics of the Spiritual Life (IVP, 1979).

[2] Rationalize or rationalization is the sociological concept from Max Weber to describe the movement from a charismatic movement to rational structures, forms, laws, and institutions to preserve the “movement.”

Dr. Scott W. Sunquist, President of Gordon-Conwell Theological Seminary, is author of the “Attentiveness” blog. He welcomes comments, responses, and good ideas.

Dr. Scott W. Sunquist, President of Gordon-Conwell Theological Seminary, is author of the “Attentiveness” blog. He welcomes comments, responses, and good ideas.