We are all “Others”

DR. TODD M. JOHNSON

PROFESSOR OF GLOBAL CHRISTIANITY AND MISSION

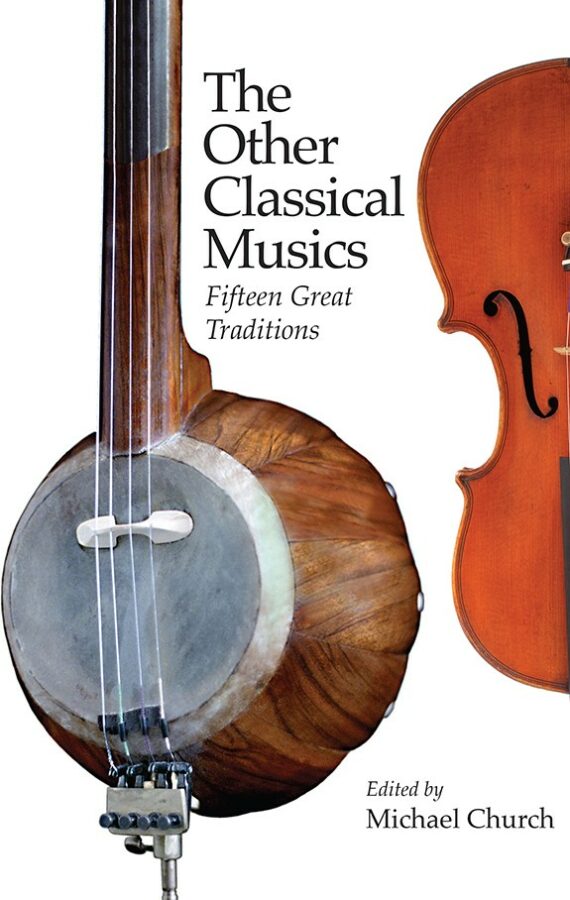

Some time ago, I picked up a copy of The Other Classical Musics, thinking that it was about non-Western classical music. Sure enough, the first few chapters were on music in Thailand, Indonesia, Japan, China, India and Africa. But there was also a chapter on North American Jazz, and another on European classical music. The editor writes, “‘Other’ simply refers to all the musics beyond each reader’s native culture, be that in Beijing or Birmingham, Tehran or Tokyo. Thus is Western classical music brought level with the rest” (Church, 2). In other words, the book posits that all classical musics are “others” because there is no central standard by which all ‘others’ are measured, certainly not European classical music. What a profoundly beautiful way to recenter this conversation on global classical music. All are equal: every culture is qualified as an “other” because of our different set of standards.

This reminds me of the central tenet of World Christianity, that no one culture can claim to represent the Christian faith. The late Scottish missiologist Andrew Walls captured this in what he called the “indigenizing principle”: Each culture has equal access to the gospel and offers unique perspectives on the global faith, The gospel goes deep within each culture of the world. Walls wrote, “World Christianity is not a development of the last century; it is the natural Christian condition. Christianity has always been global in principle, and for much of its history, global in practice too. And global inevitably means multicultural. Cultural diversity was built into the church within the New Testament period” (Walls 2010, 18). We have this expectation because “from one man God made every nation of the human race, that they should inhabit the whole earth” (Acts 17:26).

At the same time, thousands of cultures are reconciled to one another where “there is neither Jew nor Greek, slave nor free, male nor female, for you are all one in Christ Jesus” (Gal 3:28). Walls’ “pilgrim principle” states that everywhere Christians are in unity because we have in common our heavenly home. Putting these two principles together, Walls states, “But the very diversity was part of the church’s unity. The church must be diverse because humanity is diverse; it must be one because Christ is one. Christ is human, and open to humanity in all its diversity; the fulness of his humanity takes in all its diverse cultural forms. Believers from the different communities are different bricks being used for the construction of a single building—a temple where the One God would live” (Eph. 2:19-22) (Walls 2002, 76–77).

Unfortunately, this unity in diversity is not what happens most of the time in our churches and our societies around the world. Instead, we practice “othering,” a phenomenon in which some individuals or groups are defined and labeled as not fitting in within the norms of a social group. It is an “us vs. them” perspective about human connections and relationships that involves looking at others and saying, “They are not like me,” or “They are not one of us.” This way of navigating diversity destroys the unity of both the church and our human family.

What can we do to fight “othering”? The editors of VeryWellMind.com offer this helpful advice: “People tend to seek others that are like them, but it can be helpful to seek out friendships and social connections with people from diverse backgrounds. Conflict and prejudice can be reduced when people who belong to different groups spend time with one another.” This underlines the importance of leading with friendship and hospitality to build unity both in global Christianity and in the global human family. For example, social psychologist Christena Cleveland writes, “If Christians focus on similarities between themselves and culturally different Christians and keep in mind that their identity as Christians is more important than other cultural identities, then they should naturally begin to like culturally different Christians.” (Cleveland, 75) Cindy Wu and I tried to build on this when we noted: “Christians see ways in which they differ (ethnicity, language, denomination) as well as ways in which they are the same (practice, core theology, creeds). When we adopt a common global identity we begin to tear down cultural divisions and work toward reconciliation” (Johnson and Wu, 98). This pilgrim perspective on identity supports a truly global view of the human family.

As John Powell writes “The opposite of othering is not “saming”, it is belonging. And belonging does not insist that we are all the same. It means we recognise and celebrate our differences, in a society where ’we the people’ includes all the people.” In the end, othering cannot exist if we believe that we belong to the same family (both as humans and as Christians). We are all pilgrims. As pilgrims, we are all “others.”

- Church, Michael. The Other Classical Musics: Fifteen Great Traditions. Boydell Press, 2015.

- Cleveland, Christena. Disunity in Christ: Uncovering the Hidden Forces That Keep Us Apart. Downers Grove, Illinois: IVP Books, 2013.

- Johnson, Todd M., and Cindy M. Wu. Our Global Families: Christians Embracing Common Identity in a Changing World. Grand Rapids, Michigan: Baker Academic, 2015.

- Walls, Andrew F. The Cross-Cultural Process in Christian History: Studies in the Transmission and Appropriation of Faith. Maryknoll, N.Y: Orbis Books, 2002.

- Walls, Andrew F. “World Christianity and the Early Church,” in A New Day: Essays on World Christianity in Honor of Lamin Sanneh, edited Akintunde E. Akina, New York: Peter Lang, 2010.