What is “The Columba Option,” and Who Was Saint Columba?

Wendy Murray

In yesterday’s post, Dr. Currie made reference to the idea of Christians appropriating “The Columba Option,” reflecting the spirituality of this little-known saint. What does that mean? Who was Columba? What might that “option” look like?

In short, Columba was an Irish poet who lived during the sixth century and who ended up in exile on the nondescript Isle of Iona off the western coast of what is now Scotland. He had been embroiled in a violent skirmish involving, of all things, the place of the poets in Irish society.

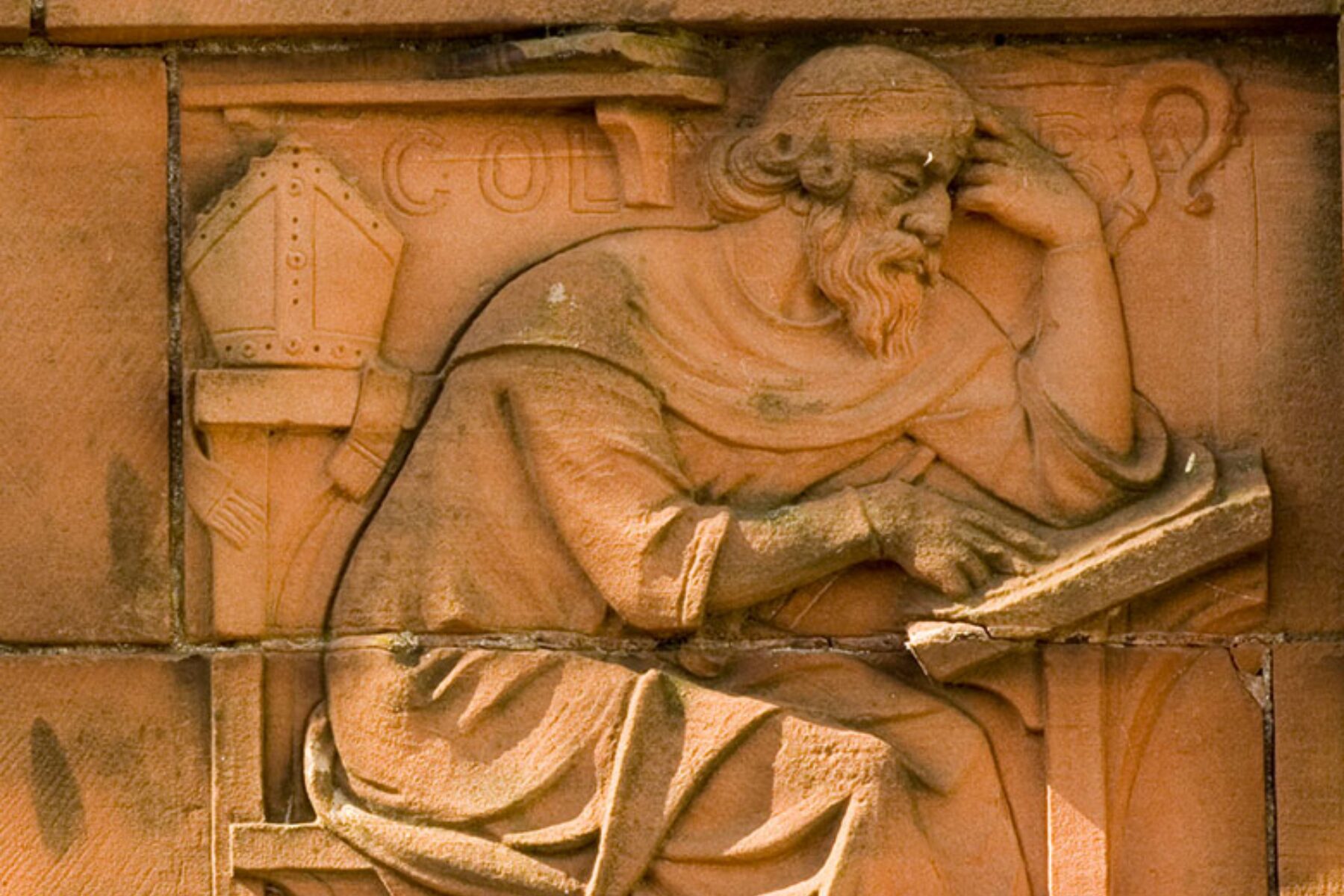

He came from a line of kings who had ruled in Ireland for centuries and was himself in close succession to the throne. He was raised by priests and in time renounced his rank to become “a religious” (a friar). By his mid-20s he had founded several monasteries in Ireland, including the well-known Abbey at Kells.

It has been estimated that, in sixth-century Ireland, approximately one third of the population were poets. Columba, being a man of letters, found himself at the center of a controversy that resulted in a devastating turn of events for him. Historians differ on the specifics of what happened, though it is widely believed that he had copied a portion from the gospels, or possibly a psalm, from the rare single copy of the Scriptures on site at the abbey where he was living. Having copied it himself (an arduous, thankless undertaking), he intended upon keeping it, whereas the king at the time claimed it belonged to the abbey from which it had been copied. (The written word, in those days, was a priceless treasure.) In defense of his rights to it, Columba found himself at the center of a melee that broke out among the Irish clans in which thousands were slaughtered.

Filled with remorse after the bloodshed, Columba underwent a profound change of heart and, as a result, chose exile for himself. He left Ireland–the land he so loved and that inspired his poet’s pen–and set sail with a dozen companions, landing on Iona, in what is now called the Inner Hebrides. (It is said he was far enough away from his beloved Ireland to be deemed an exile but still able to see its coastline.) He founded an abbey there and went on to spread Christianity among the northern Pictish kingdoms (in modern-day north east Scotland). In time, his efforts changed the landscape of Scotland and, it could be argued, even Britain.

Before he died in the late sixth century, he returned to his native Ireland to take part in the assembly of Druim-Cetta in Ulster. During the assembly, Columba defended the rights of the Order of Bards (poets), claiming that the future of Gaelic culture demanded that their work be preserved:

For you know that God himself bought three-fifties of Psalms of praise from King David . . . . And on that account it is right for you to buy poems of the poets and to keep the poets in Ireland.

As all the world is but a fable,

it were well for you to buy a more enduring fable . . .

If poets’ verses be but fables

So be food and garments fables,

So is all the world a fable,

So is man of dust a fable.[1]

One of his followers said of him in the aftermath of his death, “he made a vigil of his life, everywhere a pillar of learning, light of the north, who brightened the west, and inflamed the east.”[2]

It is a testament to the global impact of this insignificant isle and the power and influence of its champion, that 200 years after Columba’s death, the mighty and conquering Vikings made their way to the beaches of Iona to hunt down Columba’s faithful band and defile his memory by ransacking his grave. His devoted followers refused to give up the location of his mortal remains, and, as payment for their devotion, were slaughtered on the white sands of that beach.

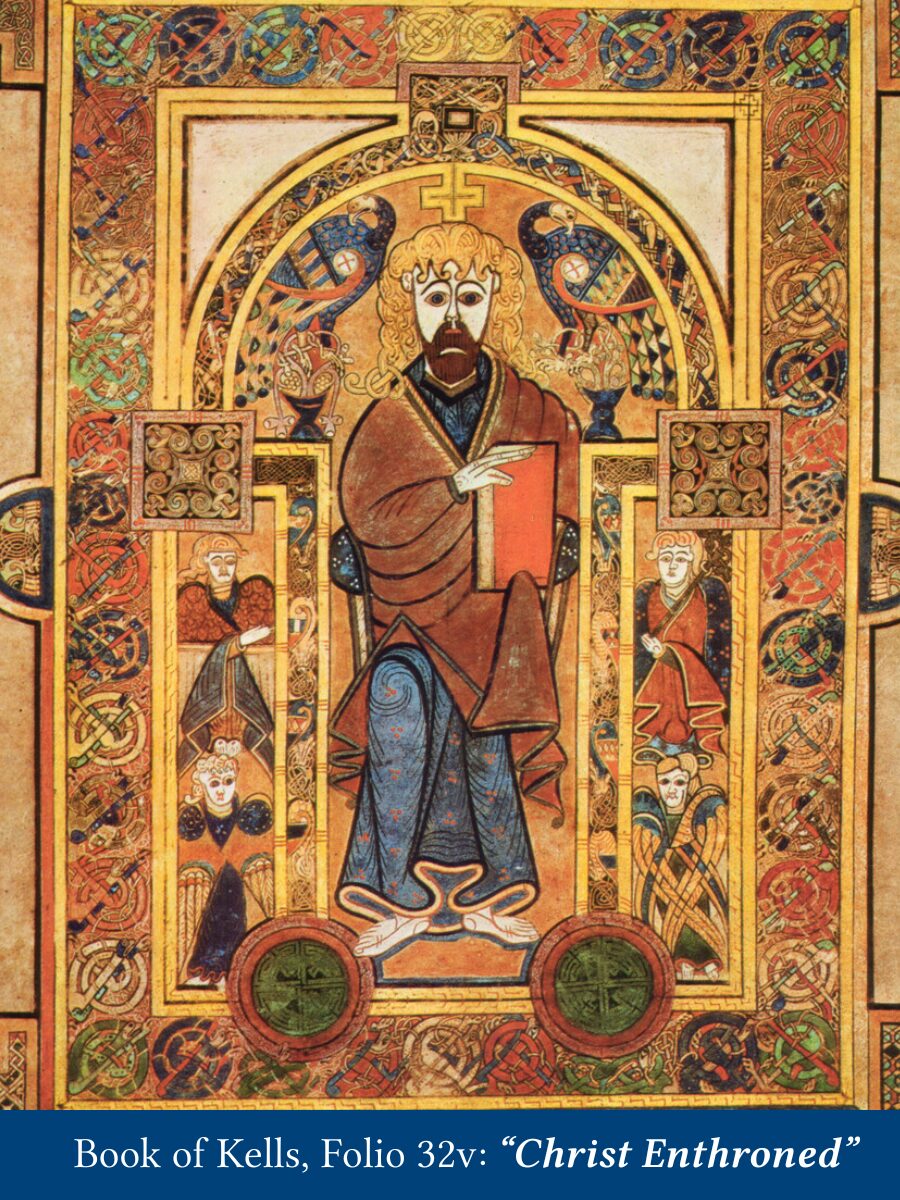

Why did the monks on his lonely isle choose death rather than give up their champion to the heathen Vikings who cared not for honor or glory, but simply meant to defile the honor of his memory? What of the miraculous book—a masterpiece of devotion, artistry, discipline, and transcendent vision—the Book of Kells, through which he trained his students? Why were the heathen Picts converted at his urging? How did he travel so far into the impenetrable Scottish Highlands where the land alone could shatter a man? And why have the saints and poets re-echoed his name throughout the ages?

Why did the monks on his lonely isle choose death rather than give up their champion to the heathen Vikings who cared not for honor or glory, but simply meant to defile the honor of his memory? What of the miraculous book—a masterpiece of devotion, artistry, discipline, and transcendent vision—the Book of Kells, through which he trained his students? Why were the heathen Picts converted at his urging? How did he travel so far into the impenetrable Scottish Highlands where the land alone could shatter a man? And why have the saints and poets re-echoed his name throughout the ages?

He came—poet, warrior, angel-spirit—and softened the desolate hearts of warrior pagans, who, before his coming, lived and died for the little power they could exact from their petty kingdoms. In exchange, he gave them the keys to the eternal kingdom, and they received it. He changed the landscape of his times—and their world, which nudged into light the landscape of our own times and our world. We bear a light because of his efforts: a single, solitary life, who carried the banner of the name of Jesus and who brought the warring tribal kingdoms of the west with him. What are we to make of him? And the greater question that is foisted upon us: what are we to make of ourselves, who grow weary under far lesser burdens?

He made a vigil of his life, he was a pillar of learning, light of the north who brightened the west, and inflamed the east—perhaps this is the picture of “The Columba Option.”

[1] Brian Lacey, Colum Cille and the Columban Tradition, Dublin: Four Courts Press, 1997.

[2] Ibid.

Wendy Murray is the associate director of accreditation and communications. She is working on a book on Scottish history and especially the role of the Murray clan. Her book, The Franciscan Way, will be out next year with Paraclete Press.