Resonating with Art and the Divine Artist

Dr. Wes Vander Lugt

“I don’t like it. I don’t understand it. It just doesn’t do it for me.”

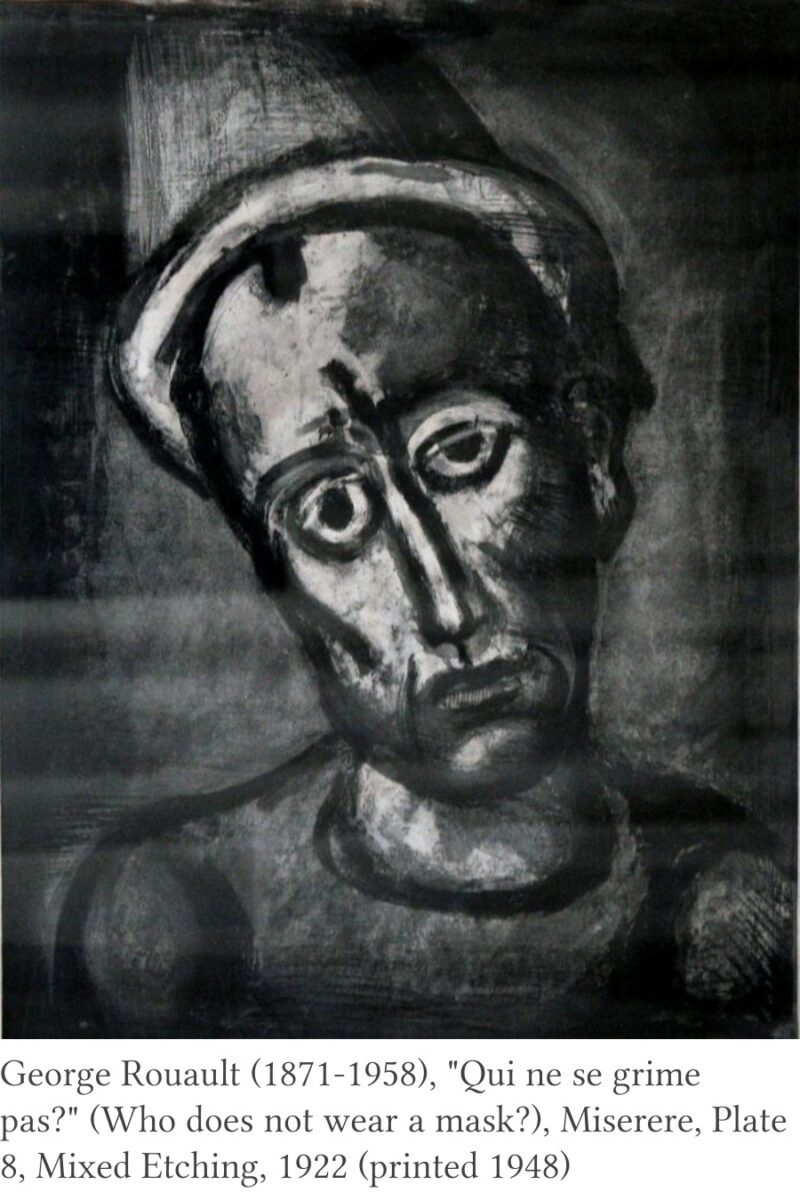

If you have ever responded in one of these ways to modern and contemporary visual art, you are not alone. Modern art can be bewildering, and it can be difficult to discern its theological significance, even with an artist of faith like George Rouault, whose work was recently on display at the Charlotte campus. The good news is that we can all learn how to cultivate resonance with art where it may not naturally exist. As we explored in the recent symposium on the art of Georges Rouault, learning to do so is a spiritually formative practice.

Resonance describes a vibrant connection with something or someone, producing receptivity, responsiveness, and transformative connection. Sociologist Harmut Rosa describes it as “an energetically charged form of contact,” whereas the opposite of resonance is the alienating experience of indifference, disconnection, and dullness.[1] To experience resonance with a work of art, therefore, means the art will “speak” to you in some transformative way. Whether or not this emerges naturally, I believe resonance with art can be cultivated through availability, perception, and response. In turn, this enables us to cultivate resonance with the beauty of God in Christ and in all his diverse image bearers.

The first step in cultivating resonance with an artwork such as Rouault’s “Who does not wear a mask?” is the decision to be fully present and available to whatever it has to offer. The average viewer spends fifteen seconds before an artwork, which is rarely enough time to experience resonance. We need to learn how to be present, which is why the Slow Art movement exists: to help us embrace the simple, joyful act of slowing down and looking. The challenge is to spend ten minutes gazing at each artwork, and to understand that “what sounds like a possibly boring act (if watching paint dry is boring, then watching dry paint must be even more so), is quite the opposite.”[2] Committing to be present and available—whether before an artwork, before another person, or before God’s revelation—is the doorway to transformative encounters.

The first step in cultivating resonance with an artwork such as Rouault’s “Who does not wear a mask?” is the decision to be fully present and available to whatever it has to offer. The average viewer spends fifteen seconds before an artwork, which is rarely enough time to experience resonance. We need to learn how to be present, which is why the Slow Art movement exists: to help us embrace the simple, joyful act of slowing down and looking. The challenge is to spend ten minutes gazing at each artwork, and to understand that “what sounds like a possibly boring act (if watching paint dry is boring, then watching dry paint must be even more so), is quite the opposite.”[2] Committing to be present and available—whether before an artwork, before another person, or before God’s revelation—is the doorway to transformative encounters.

The second step in cultivating resonance is to move beyond looking to perceiving. Anyone can look at “Who does not wear a mask?” and say they’ve seen it, but have they really perceived it? As Marguerite Duras once said, “the art of seeing has to be learned,”[3] which often happens through dialogue and the sharing of perspectives like we experienced at the Rouault symposium. With perception, context is key, including the context of an artist’s life and work as a whole. For example, our perception grows when we learn of Rouault’s encounter with a clown while travelling with a nomad caravan and his realization that “the ‘clown’ was me, was us, nearly all of us . . . we are all more or less clowns, we all wear a glittering costume.”[4] The artwork may not be “pleasing” on the surface, but the process of perception leads us beneath the surface toward a deeper discernment of meaning and self-discovery.

A final step in cultivating resonance with an artwork is response, which is more robust than reaction, since it involves what Rosa calls “adaptive transformation” in other areas of life.[5] What kind of adaptive transformation might happen when you meet the gaze of Rouault’s clown and experience resonance there? Might this engender a compassionate response when meeting the gaze of real neighbors whose “mask” you deem marginal or unpleasant? How might cultivating resonance with the etched face and eyes of this clown prepare us to find resonance with the Christ who, as Gerard Manley Hopkins poetically expressed, “plays in ten thousand places, / Lovely in limbs, and lovely in eyes not his.”[6] Furthermore, how might we respond with attentiveness to our own identity and self-discovery as mask-wearers who, to use the language of the apostle Paul, are invited to “put on Christ?”[7] What does it look like to take off the mask of the old self and put on the new self, not as hypocrites, but as those longing to be true to who we are already are by an act of grace?[8]

Resonance emerges as we move from availability and perception to response. Learning to resonate with art like Rouault’s is an ongoing gift, offering surprising insight and adaptive transformation for cultivating resonant relationships in everyday life and with a God who is present in unlikely places.

[1] Rosa, Resonance, 285-86.

[2] Lines from Gerard Manley Hopkins, “As Kingfishers Catch Fire.”

[3] Romans 13:14; Galatians 3:27; Colossians 3:12

[4] Ephesians 4:24; Colossians 3:10

[5] Hartmut Rosa, Resonance: A Sociology of our Relationship with the World, translated by James C. Wagner (Medford, MA: Polity Press, 2019), 137.

[7] Quoted in Anne Bogart, The Art of Resonance (New York: Menthuen Drama, 2021), 55.

[8] Quoted in Franco Mormando, “Of Clowns and Christian Conscience,” America 199, no. 17 (2008): 18.

Dr. Wes Vander Lugt serves as an Adjunct Professor of Theology at Gordon-Conwell and co-founder of Kinship Plot. His publications include Living Theodrama: Reimagining Theological Ethics, which uses theatre as a holistic model for integrating spiritual formation and faithful action, and other books and essays on theology and the arts and spiritual formation.

Dr. Wes Vander Lugt serves as an Adjunct Professor of Theology at Gordon-Conwell and co-founder of Kinship Plot. His publications include Living Theodrama: Reimagining Theological Ethics, which uses theatre as a holistic model for integrating spiritual formation and faithful action, and other books and essays on theology and the arts and spiritual formation.