Visualizing Christian Martyrdom

DR. TODD M. JOHNSON

PROFESSOR OF GLOBAL CHRISTIANITY AND MISSION

One of the most rewarding and challenges aspects of my research has been teaching Christian martyrdom, or more specifically, describing the demographic situation of persecution and martyrdom around the world from the time of Christ to the present. Probably our most seminal contribution to this field is our much-cited statistic that more Christians were killed in the 20th century than in all the previous centuries combined. This week I am presenting a plenary talk on “Teaching Christian Martyrdom” at the annual meeting of the Association of Professors of Mission. I’m looking forward to interacting with my colleagues on this important topic.

As a person who specializes in statistics, I learned early on in my teaching that visualization is essential to communicating the meaning behind the numbers. In teaching martyrdom, visualizations of various kinds can play a helpful role. What follows are a few examples that I use in my own lectures. First, artwork plays a central role, and some of our most famous artists painted scenes of martyrs and martyrdom. For example, “The Stoning of Saint Stephen” is the first signed painting by Dutch artist Rembrandt, painted in 1625 at the age of 19. This work is inspired by the martyrdom of Stephen, which is recounted in Acts 7.

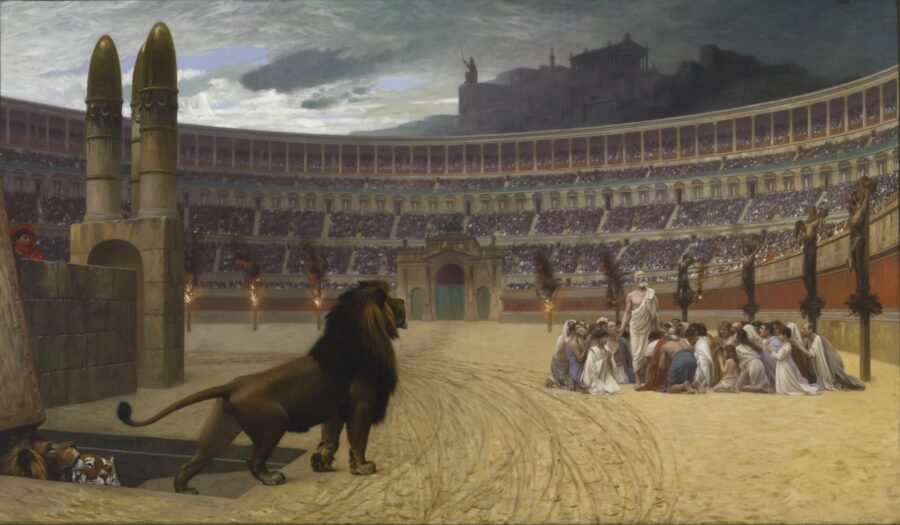

Another well-known painting is Jean-Leon Gérôme’s “The Christian Martyrs’ Last Prayer,” painted in 1883. Gérôme identified the setting as ancient Rome’s racecourse, the Circus Maximus. He noted such details as the goal posts and the chariot tracks in the dirt. The seating, however, more closely resembles that of the Colosseum, Rome’s amphitheater, in which gladiatorial combats and other spectacles were held. The hill in the background surmounted by a colossal statue and a temple is nearer in appearance to the Athenian Acropolis than it is to Rome’s Palatine Hill. Gérôme, whose paintings were usually admired for their sense of reality, has subordinated historical accuracy to drama.

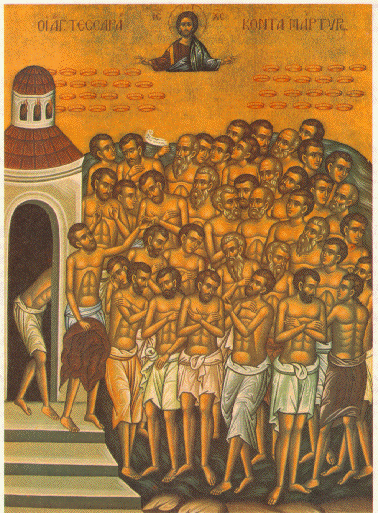

Christian icons of the martyrs are closely related to art. One of the most well-known is The Forty Martyrs of Sebaste (say-bast), or the Holy Forty. These were a group of Roman soldiers whose martyrdom in 320 for the Christian faith is recounted in traditional martyrologies. According to Basil, 40 soldiers who had openly confessed themselves Christians were condemned by the prefect to be exposed naked upon a frozen pond near Sebaste on a bitterly cold night, that they might freeze to death. Among the confessors, one yielded and, leaving his companions, sought the warm baths near the lake. One of the guards was set to keep watch over the martyrs and beheld at this moment a supernatural brilliancy overshadowing them. He at once proclaimed himself a Christian, threw off his garments, and joined the remaining thirty-nine. At daybreak, the stiffened bodies of the confessors, which still showed signs of life, were burned and the ashes cast into a river. Perhaps it would be good to mention at this stage that storytelling can match very well with good artwork or icons.

A contemporary icon is the 21 Coptic martyrs. On 12 February 2015, the Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant (ISIL) released a report in their online magazine Dabiq showing photos of 21 Egyptian Coptic Christian construction workers that they had kidnapped in the city of Sirte, Libya, and whom they threatened to kill. Three days later, a five-minute video was published, showing the beheading of the captives on a beach along the southern Mediterranean coast. We used this icon on the cover of our book Christianity in North Africa and West Asia.

I have also used film clips in teaching martyrdom, particularly in class with students. One of the most effective for me is The Passion of Joan of Arc, a silent film produced in France in 1928 based on the record of the trial of Joan of Arc. The film was directed by Carl Theodor Dreyer and stars Renée Falconetti. Her portrayal is widely considered one of the most astonishing performances ever committed to film, and it would remain her final cinematic role. Dreyer’s method of directing his actors pushed Falconetti to emotional collapse. The original version of the film was lost for decades after a fire destroyed the master negative and only variations of Dreyer’s second version were available. In 1981, an employee of a psychiatric hospital in Oslo found several film canisters in a janitor’s closet that were labeled “The Passion of Joan of Arc.” Composer Richard Einhorn later produced a soundtrack with Anonymous 4 as the voice(s) of Joan of Arc. In the 1990s, I witnessed a live presentation of this music synced with the film—a profoundly moving experience.

These examples of art, icons, and film show that visualizing Christian martyrdom is a helpful aid to teaching Christian martyrdom. Beyond giving students something to look at during a lecture, each of these images has its own story and offers insights into historical perspectives on Christian martyrdom. Let us hope that visualizing martyrdom will give both an accurate and compelling account of this ongoing witness of Christians around the world.

Photo credits:

Rembrandt: Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=15686766

Gerome: https://art.thewalters.org/detail/36782/the-christian-martyrs-last-prayer/

Forty Martyrs of Sebaste: The Orthodox Weekly Bulletin, http://web.mit.edu/ocf/www/icons.html

21 Coptic Martyrs: https://legacyicons.com/21-new-martyrs-of-libya-icon-s100/

The Passion of Joan of Arc: https://www.tcm.com/tcmdb/title/328534/the-passion-of-joan-of-arc/#overview