Justice for all Peoples

DR. TODD M. JOHNSON

PROFESSOR OF GLOBAL CHRISTIANITY AND MISSION

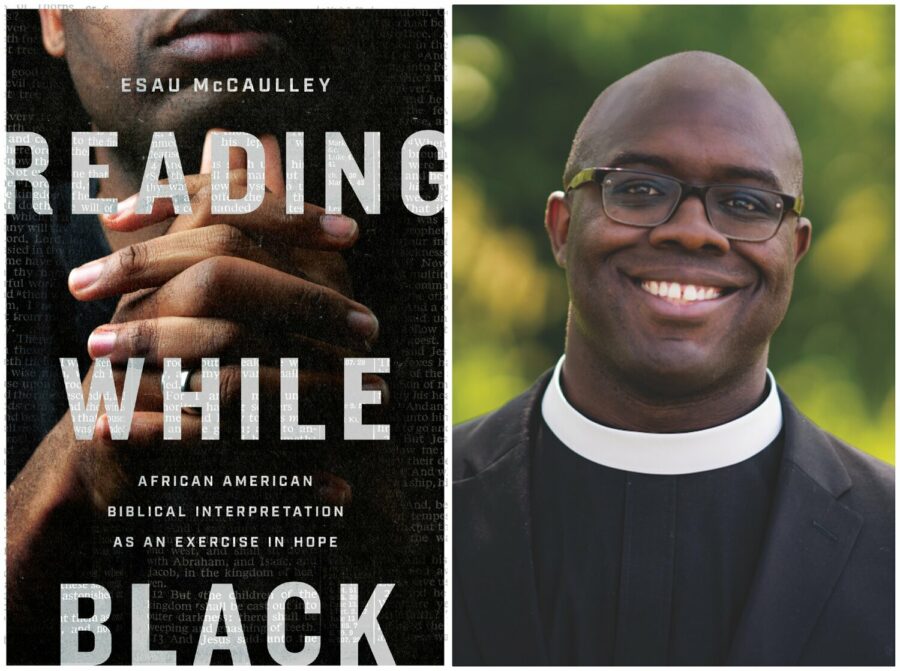

Earlier this month, we had a faculty colloquium with Dr. Esau McCaulley on his book, Reading While Black: African-American Biblical Interpretation as an Exercise in Hope. Having read his book last year as I was preparing a talk for the Evangelical Missiological Society on “Evangelical mission in an age of global Christianity,” I was grateful to participate as a faculty respondent with Dr. McCaulley joining on Zoom. Since my area of expertise is demographics, I began my response by noting that from only 8% in 1900, today Black, indigenous, and people of color represent 77% of all Evangelicals worldwide. This reality runs against the popular perception that the United States is the ‘home’ of contemporary Evangelicalism, where it is perceived as a largely White, politically conservative movement. Evangelicals globally are generally concerned with poverty, justice, immigration and social welfare whereas White Evangelicals tend to focus on sexuality and abortion with seemingly little interest in racial justice. Or as Dr. McCaulley writes, “But what about the exploitation of my people? What about our suffering, our struggle? Where does the Bible address the hopes of Black folks, and why is this question not pressing in a community that has historically been alienated from Black Christians?” (p. 12) Dr. McCaulley’s question reverberates still in the global Evangelical community.

McCaulley offers a strong biblical rationale for justice for all peoples. He opened my eyes to some fresh perspectives on both the Abrahamic and Davidic covenants and the global gathering of the peoples in Revelation 7:9. My own reading of these texts has been deeply shaped by the frontier mission movement, in which these texts emphasize God’s love for all peoples and therefore, point to a priority on mission to peoples previously unfamiliar with the gospel. Rightly so. But as Dr. McCaulley points out, these passages also speak of equality and justice for all peoples. He writes, “What do Abraham and David together mean for the Black and Brown bodies spread throughout the globe? It means that the vision of the Hebrew Scriptures is one in which the worldwide rule of the Davidic king brings longed-for justice and righteousness to all people groups.” (p. 105) Because the biblical view of righteousness is global, wherever the gospel goes, so goes the hope for equity and justice for all peoples. Typical White exegesis, which is generally centered in wealth, privilege, and power, often is blind to these themes woven throughout the Scriptures. With crystal clarity, Dr. McCaulley writes,

“Hungering and thirsting for justice is nothing less than the continued longing for God to come and set things right. It is a vision of the just society established by God that does not waver in the face of evidence to the contrary. Mourning is not enough. We must have a vision for something different. Justice is that difference. Jesus, then, calls for a reconfiguration of the imagination in which we realize that the options presented to us by the world are not all that there is. There remains a better way and that better way is the kingdom of God.” (p. 66)

The global gospel call that compels believers to go to the ends of the earth to fulfill Christ’s vision for representation of all peoples compels an equal commitment to Christ’s vision for biblical justice for all peoples.

These passages also legitimate theological perspectives from all peoples. Since all theology is contextual, all contexts have an equal voice in describing the Christian faith. That is freeing for Black, indigenous, and people of color because they have been told, in so many Orwellian words, that some theologies are more equal than others. White theology, in particular, locates itself at the center of the Christian story. But these biblical passages don’t allow that. Dr McCaulley writes, “Our distinctive cultures represent the means by which we give honor to God. He is honored through the diversity of tongues singing the same song. Therefore inasmuch as I modulate my blackness or neglect my culture, I am placing limits on the gifts that God has given me to offer to his church and kingdom. The vision of the kingdom is incomplete without Black and Brown persons worshiping alongside white persons as part of one kingdom under the rule of one king.” (p. 115-116) This vision is much more compelling than the world’s peoples singing White hymns or choruses.

If one culture dominates and claims to be the standard perspective, all cultures suffer. The way forward in standing against racism in the United States is to embrace the equality of all peoples found clearly in the scriptures. A global view of the gospel will help to unmask and dismantle structural racism and put us on a path to the promises of justice for all peoples.