Local vs. Global Evangelicalism

DR. GINA A. ZURLO

CO-DIRECTOR, CENTER FOR THE STUDY OF GLOBAL CHRISTIANITY

Last week I had the pleasure of guest lecturing at Dr. Chris Evans’ History of American Evangelicalism course at Boston University School of Theology. Beyond my love for my alma mater, I jumped on this opportunity because I was eager to provide students a global perspective on the Evangelical movement and to clear some of the confusion about the relationship between Evangelicalism in the United States and the movement more broadly.

In short, the social concerns of Evangelicals in the United States are generally not those of Evangelicals elsewhere in the world.

Admittedly, studying Evangelicalism globally can be potentially confusing. Originating in Europe, the movement spread to America and then to the rest of the world. As a result, Evangelicals have always been found within a wide range of denominations, there’s a lot of overlap with the Pentecostal/Charismatic movement, and there are many disagreements about who is “in” and “out” of the Evangelical movement.

Mark Hutchison and John Wolffe describe global Evangelicalism as “a historical convergence of convictions that link personal experience with universal mission,” and they add that the term “Evangelical” is not a primary identity of Christians in the global South. Rosemary Dowsett and Samuel Escobar, while emphasizing the great diversity of global Evangelicalism, assert that the term unites those in “fellowship in a spiritual bond based upon personal faith in the Lord Jesus Christ, a desire to be shaped by the Scriptures and a commitment to obedience to Christ’s missionary mandate.”

Yet, Donald M. Lewis goes as far to say there is no such thing as a singular “Evangelicalism,” but instead a variety of “Evangelicalisms.” One of the most helpful books in understanding this perspective is Donald Lewis and Richard Pierard’s Global Evangelicalism: Theology, History & Culture in Regional Perspective, an edited volume that describes Evangelicalism around the world as a grassroots movement that is indeed difficult to track and organize. Lewis and Pierard illustrate the history of Evangelicalism in Asia, Africa, and Latin America as simply the history of Protestantism itself. Particularly reflective of this view is in Latin American Christianity, where in most cases one is either Catholic or not Catholic – the latter meaning some combination of Protestant, Evangelical, Pentecostal, Charismatic, or evangélico.

The last work in this mini literature review is Brian Stanley’s The Global Diffusion of Evangelicalism: The Age of Billy Graham and John Stott. Stanley makes the important observation that the global South does not have the same Enlightenment backdrop as the global North. Instead, the social backdrop is one of poverty, hunger, disease, and injustice. Indeed, we’ve found that the rapid growth of Christianity – and Evangelicalism – in the 20th and 21st centuries has occurred in places where people generally have a much lower quality of life. For instance, in much of the global South, serious issues related to poverty and proper health care form a lived experience that results in its own interpretation of scripture, with greater emphasis on the work of the Holy Spirit and an integral Christian witness that more naturally pairs the physical and spiritual realms. Stanley concludes that the fate of global Evangelicalism depends on the global South.

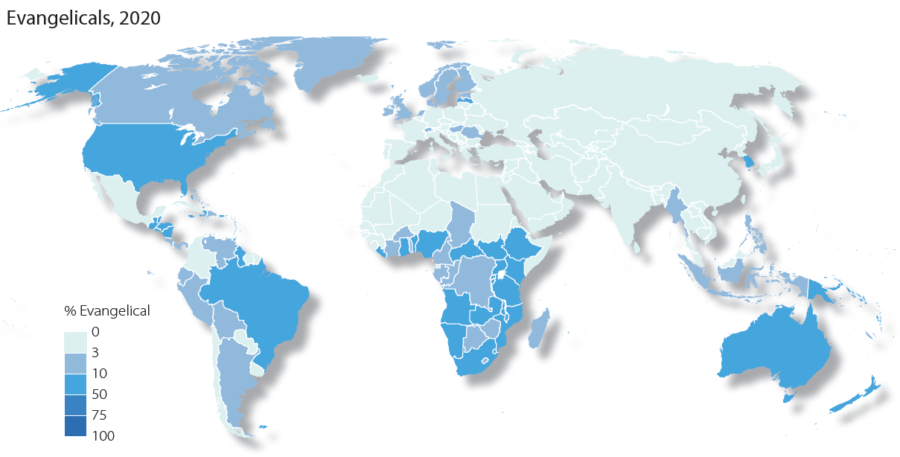

Evangelicals by country, 2020 (World Christian Encyclopedia, 3rd ed.)

What ties global Evangelicalism together? Around the world, Evangelicals share concerns for the availability of scripture, literacy and education, and missions and evangelism – all rooted in a shared theology of the centrality of Christ, the importance of Scripture in the Christian life, and local and global outreach. But how do we reconcile their differences? In the global South, we find what some Western Christians might consider more “progressive” views concerning refugees and immigration, acknowledgement of climate change, and the importance of women in the church. Meanwhile, American Evangelicalism, as of late, is popularly associated with whiteness, patriarchy, conservative Republican politics, and anti-immigrant sentiment – characteristics that are simply not those of most Evangelicals around the world. For instance, Nigerian theologian Ogbu Kalu described Evangelicalism in Africa as a subversive movement based on voluntarist principles that downplayed the pomp and powerful.

Returning to Dowsett and Escobar, we see a kind of Evangelicalism that is different from the movement in the United States: “For Latin Americans, merely pietistic faith and reductionist evangelism were a travesty of the gospel. Authentic mission must engage with the whole of life in every dimension, including issues of structural injustice, political repression, Marxism, exploitation of the poor by the powerful (who are often associated with church structures), and the acute suffering engendered by rapid urbanization and industrialization. Sin and salvation took on enlarged dimensions, without losing sight of the need for individual men and women and children to be reconciled with God through faith in Christ.”

Consequently, White Evangelicals in the USA have an opportunity to come alongside their compatriots in the global South and recover the contours of a movement that many believe has been hijacked by the American political system to the detriment of the movement’s core concern for people at the margins.

That sounds a lot closer to the example set by Jesus.