Self-Identification in Researching Christianity Worldwide

DR. GINA A. ZURLO

Co-Director, Center for the Study of Global Christianity

As a demographer of religion, I am regularly asked this question: Are Mormons and Jehovah’s Witnesses Christians? It’s often paired with a question something along the lines of: “You say there’s 2.5 billion Christians in the world, but how many of them are REALLY Christians?” The short answer is: I have no idea. That’s not my job. I’m a social scientist, not a mind-reader. Nor am I the judge of who’s in the “visible” or “invisible” church (thank goodness).

My job is to count people who self-identify as Christians. This is standard practice for sociologists of religion. That is, if someone claims to be Christian (or a Buddhist or Jew), then I consider her or him a Christian (or a Buddhist or Jew). Likewise, if a Christian group claims to be part of the global church, then they are considered as such in our taxonomy.

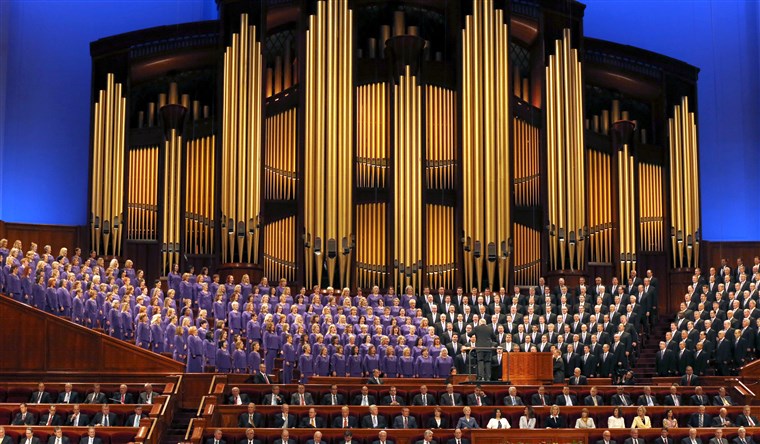

Thinking theologically for a moment, check out what these groups say about themselves. The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day Saints 13 Articles of Faith highlights belief in God, the atonement of Christ and faith in Jesus, repentance, baptism, and gifts of the Holy Spirit. Likewise, the Jehovah’s Witnesses statement of belief includes worship of one God, the Bible as God’s inspired message, Jesus as savior of the world and his ransom sacrifice. For a demographer studying all of global Christianity in its various cultural and theological forms, this is enough for me.

In our taxonomy, Latter-day Saints and Witnesses are classified as “North American Independents,” which means they are grouped with other traditions founded in the North American context as renewal movements within Christianity who self-identify as Christians. The United States in particular has had a long history of such groups, many of which surfaced in the early 1800s. Historians have often considered them “outsiders” of what is perceived as the “primary” story of American religion (read: white, male, Protestant). But if you reconsider American religious history from the “margins,” a different picture emerges.

Latter-day Saints, for example, historically were considered different from other Christians because they self-identified as different, not because they actually weredrastically different theologically or espoused different values than other Americans. Latter-day Saints were mostly middle-class Victorian, frontier Americans and in many ways no different than other 19th-century sectarian groups that arose around the same time. Mormons were quintessentially American in the sense that their religion was the most logical outgrowth of the voluntary religious system (a system where you are in control of your religious choices).

An ironic piece of Latter-day Saint history, however, is that by the 21stcentury many Latter-day Saints wanted nothing else but to be considered mainstream American Christians. When Mitt Romney ran for the Republication Party nomination in the 2008 presidential election – deemed the “Mormon moment” – the LDS church ran ad campaigns with people saying: “I’m just like you, and I’m a Mormon”. The struggle for difference in the 19thcentury had turned into a struggle for acceptance in mainstream 21st-century America.

Sectarian groups have always encouraged and enhanced religious diversity, renewal, creative, growth, and vitality. I would argue the same is true for global Christianity. One way of looking at it is this: the more diversity that exists within Christianity, the more people feel like they can join it and still remain the individuals they were created to be. For me and my job, though, the bottom line is if you consider yourself a Christian, I do too.