Frequently Asked Questions

Where do you get your numbers?

Three major sources for international religious demography are:

- Censuses where a religion and/or ethnicity question is asked

- Surveys & polls

- Data from religious communities

These data are analyzed and reconciled to arrive at the most accurate representation of a country or region’s religious make-up. For a comprehensive overview of the methodology of religious demography, see Todd M. Johnson and Brian J. Grim, The World’s Religions in Figures: An Introduction to International Religious Demography (Malden: Wiley-Blackwell, 2013).

What’s the fastest-growing religion in the world?

Between 2000 and 2010, the fastest-growing religion in the world was Islam, at 1.86% per annum. Over the same period the world’s population grew at 1.20% per annum. See table 1.1 from The World’s Religions in Figures.

Which is growing faster worldwide, Christianity or Islam?

Overall, between 2000 and 2010, Islam grew faster than Christianity. Islam grew at 1.86% per annum, whereas Christianity grew 1.31% (the world’s population grew at 1.20%). In 2010, there were 2.3 billion Christians (32.8% of the world’s population) and 1.6 billion Muslims (22.5% of the world’s population). See table 1.1 from The World’s Religions in Figures. We also released a response to the Pew Research Center’s 2015 report about the future of the world’s Muslim and Christian population, which can be viewed or downloaded here.

How do you know what’s going on in North Korea?

It is indeed challenging to assess the religious situation in North Korea, and other similarly closed countries. In difficult cases the CSGC relies on on-the-ground informants for information.

Is the United States becoming secularized?

Yes and no. The United States has seen a dramatic rise in its nonreligious (atheist and agnostic) population, from just 1.32% of the population in 1900 to 15.1% in 2010. Over the same period, Christians have dropped from 96.4% to 72.0%. However, in terms of raw numbers, Christians are still the vast majority (nearly 250 million in 2010, compared to 44.6 million nonreligious), with great potential for growth due to immigration from the global South (particularly Latin America). The disestablishment of Christianity in the United States early in its history makes the American case quite different from that of Europe.

Do you consider Mormons and Jehovah’s Witnesses Christians?

Like other sociologists of religion, the CSGC utilizes a strict methodology of self-identification. That is, if an individual claims to be Christian, then the CSGC considers him/her a Christian. Mormons and Jehovah’s Witnesses are classified as “North American Independents” in our typology. This means that they are members of traditions born in the American context as renewal movements within Christianity who self-identify as Christians.

Why do you report such high figures for Christian martyrs?

The CSGC estimates that there have been over 70 million Christians martyred in history. Over half of these were in the 20th century under fascist and communist regimes. In the early 21st century we estimate that on average over the 10-year period from 2000–2010 there were approximately 100,000 Christians killed each year (1 million total). For a detailed explanation of why, please click here.

What is your relationship with the Pew Research Center?

Like the Center for the Study of Global Christianity, the Pew Research Center’s Religion & Public Life Project is an organization that engages in worldwide religious demographic research. Pew collects data through public opinion surveys, demographic studies, and other social science research to examine the religious composition of countries, the influence of religion on politics, and other topics.

The CSGC began a partnership with Pew in 2008 with the launch of the World Religion Database. We work together to arrive at best estimates for the religious composition of countries, and Pew relies on the CSGC to provide data on smaller countries and religious traditions where no survey data are available.

While the CSGC and Pew are partners in the emerging field of international religious demography, there are some significant differences between our methodologies for counting religionists. While both groups rely heavily on government censuses and social science survey data, the CSGC also collects data from religious communities themselves, such as denominational statistics and missionary data from Christian churches and parachurch organizations. The CSGC also takes into greater consideration ethnographic and anthropological data, particularly for smaller, lesser-known groups. This often results in differences of opinion in terms of our best estimates and what is happening on the ground in many countries. One example of this is the recent Pew Research Center report on projecting the world’s religious populations to 2050. We posted our response here, where we outlined how there could be 3.4 billion Christians in 2050, much higher than Pew’s projected 2.9 billion.

We have also written a response to Pew’s recent estimate of how many Muslims there are in the United States, which can be found here.

How do you define and count Evangelical Christians?

We primarily use denominational affiliation to define and locate Evangelicals, a method that is also generally popular among social and political scientists. The World Christian Encyclopedia (Oxford University Press, 1982: 826) offered the following definition of ‘Evangelical”: “A sub-division of Protestants consisting of affiliated church members calling themselves evangelicals, or all persons belonging to Evangelical congregations, churches or denominations; characterized by commitment to personal religion (including new birth or personal conversion experience), reliance on Holy Scripture as the only basis for faith and Christian living, emphasis on preaching and evangelism, and usually on conservatism in theology.” This definition is grounded in denominational affiliation, but it also goes a step further to suggest what an Evangelical denomination might actually look like. Defining Evangelicals by denominational affiliation is helpful because it allows for analysis based on an already established structure. However, this method has two important weaknesses. First, not every congregation holds to its denomination’s official statements of faith. Second, not all individuals affiliated with “100% Evangelical” congregations or denominations are actually Evangelical.

We acknowledge that denominationalism is becoming perhaps less important in the West, and denominational divides is something not as clear-cut in other parts of the world. Therefore, we employ another method of counting Evangelicals, by self-identification: if one wants to know who or what someone is, then ask. This method is beneficial in that it bypasses the complexities of denominationalism and puts the power of definition into the hands of the actual people being studied (similar to polling about political ideology). Using this method we collect data from surveys and polls that ask about Evangelicalism, such as from the Pew Research Center and Win-Gallup International. Using these two methods we estimate around 300 million Evangelicals in the world in 2015.

For more information on counting Evangelicals, please see Gina Zurlo’s article in Evangelicals Around the World: A Global Handbook for the 21st Century.

How do you define and count Pentecostal Christians?

The case for the Pentecostal and charismatic renewal as a single interconnected phenomenon can best be made by considering a “family resemblance” among the various kinds of movements that claim to be either Pentecostal or charismatic. For the purpose of understanding the diverse global phenomenon of Pentecostalism, it is useful to divide the movement into three kinds or types. First are denominational Pentecostals, organized into denominations in the early part of the twentieth century and defined as Christians who are members of the explicitly Pentecostal denominations whose major characteristic is a new experience of the energizing ministry of the Holy Spirit that most other Christians have considered to be highly unusual. This is interpreted as a rediscovery of the spiritual gifts of New Testament times and their restoration to ordinary Christian life and ministry.

Second are Charismatics, individuals in the mainline denominations (primarily after the mid-twentieth century), defined as Christians affiliated to non-Pentecostal denominations (Anglican, Protestant, Catholic, Orthodox) who receive the experiences above in what has been termed the charismatic movement.

Third are Independent Charismatics, those who broke off of denominational Pentecostalism or mainline denominations to form their own networks. While the classification and chronology of the first two types is straightforward, there are thousands of churches and movements that “resemble” the first two types but do not fit their definitions. These constitute a third type and often predate the first two types.

Pentecostals and charismatics are located globally by using a taxonomy of the world’s denominations. First, each major tradition of Christianity (Roman Catholic, Orthodox, Independent, Protestant) is sub-divided into minor traditions (e.g., Protestants as Lutherans, Baptists, Presbyterians, etc.). Pentecostals and charismatics appear within denominations in three ways. First, among Protestants, are classical Pentecostal denominations; second, Pentecostals outside of the Western world; third, charismatic individuals within non-Pentecostal denominations. We estimate around 600 million Pentecostal/charismatic Christians in the world in 2015.

For more information on counting Pentecostals, please see Todd Johnson’s article in the journal Pneuma, “Counting Pentecostals Worldwide,” Vol. 36 (2014): 265–288.

How much money is embezzled every year in the global Christian community?

In 2015, an estimated USD 50 billion will likely be stolen from money that Christians give to churches, para-church organizations, and secular organizations all over the world. A recent Association of Certified Fraud Examiners (ACFE) reported stated that the US economy loses approximately 6% of its Gross Domestic Product to fraud each year, or approximately USD 660 billion. Applying the ACFE findings above to Christian giving, it is plausible that in 2015, approximately USD 50 billion, or 6% of all funds given by Christians globally (USD 850.9 billion), will be lost to fraud and embezzlement (USD 46 billion from specifically Christian organizations). Fraud in the non-profit sector might also be on the rise; consequently, these current figures could be considered quite conservative, and by the year 2025 global embezzlement of giving by Christians might be as high as 10%, or USD 100 billion.

For more information on embezzlement, see Todd Johnson, Gina Zurlo, and Albert Hickman’s article, “Embezzlement in the Global Christian Community,” The Review of Faith and International Affairs (June 2015).

What percentage of pastors worldwide have theological training?

The CSGC estimates a total of 5 million pastors/priests in all Christian traditions worldwide (Catholics, Orthodox, Protestants, and Independents, including bi-vocational). Of these, we estimate that 5% (250,000) are likely to have formal theological training (undergraduate Bible degrees or Master’s degrees). This is based on incomplete responses in survey results from colleges and seminaries in our Global Survey on Theological Education. Roughly 70% of these pastors are in Independent congregations. Independent pastors, in particular, have little theological training, even in the West.

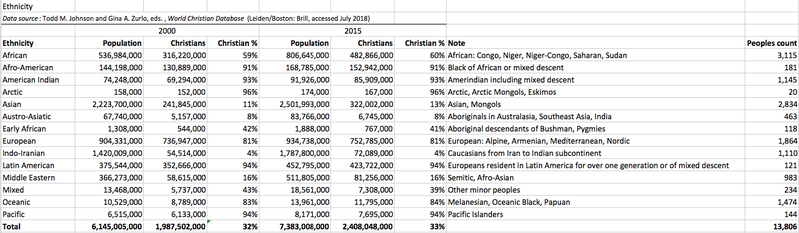

What is the ethnic makeup of world Christianity?

The CSGC maintains a database of over 13,000 ethnolinguistic peoples, found in the World Christian Database. Not all combinations of ethnicity and language are possible, but nevertheless, every person in the world can be categorized as belonging to a mutually exclusive ethnolinguistic people. For example, there are ethnic Kazaks who speak Kazak as their mother tongue and ethnic Kazaks who speak Russian as their mother tongue. These are two separate ethnolinguistic peoples. Because of this database of peoples, the CSGC can estimate the ethnic breakdown of world Christianity, as follows, for 2015:

In 2000, 62% of Christians globally were of color (1.2 billion). In 2015, 68% of Christians are of color (1.6 billion).

What is the ethnic makeup of Evangelicalism?

Globally, Evangelicalism is a predominantly non-white movement within Christianity. In 2000, 79.1% of all Evangelicals were of color (non-white; 185.2 million). In 2015, 84.1% of all Evangelicals in the world are of color (non-white; 270.1 million).

The United States is an outlier in that Evangelicalism is a majority-white movement within Christianity. In 2000, 39.6% of all Evangelicals in the USA were non-European (19.0 million). In 2015, 41.2 of all USA Evangelicals were non-European (20.9 million). There is a serious scholarly debate about the relationship of African Americans to Evangelicalism, especially after the 2016 presidential election where 81% of white Evangelicals and 8% of African Americans voted for Donald Trump. African Americans have long been excluded from sociological and political discussions of Evangelicalism because of the perception that Evangelicalism is a white phenomenon. In reality, African American Christianity generally adheres to the theological characteristics of historical Evangelicalism. In general, sociologists consider African American Christianity as separate from Evangelicalism under the golden rule of self-identification: the community does not self-identify as part of the movement. However, many historians and theologians consider African Americans Evangelicals based on their beliefs and religious practices. The Center for the Study of Global Christianity does not include African Americans in its reporting on Evangelicalism in the USA based on self-identification (they generally do not call themselves Evangelicals) and because the patterns of religiosity (belief, practice, affiliation) vary so significantly from white Evangelicals.

How do you define a "denomination"?

130 Essex St. | South Hamilton, MA 01982

Phone: 978-468-2750 | Fax: 978-468-1549 | E-mail

@CSGC